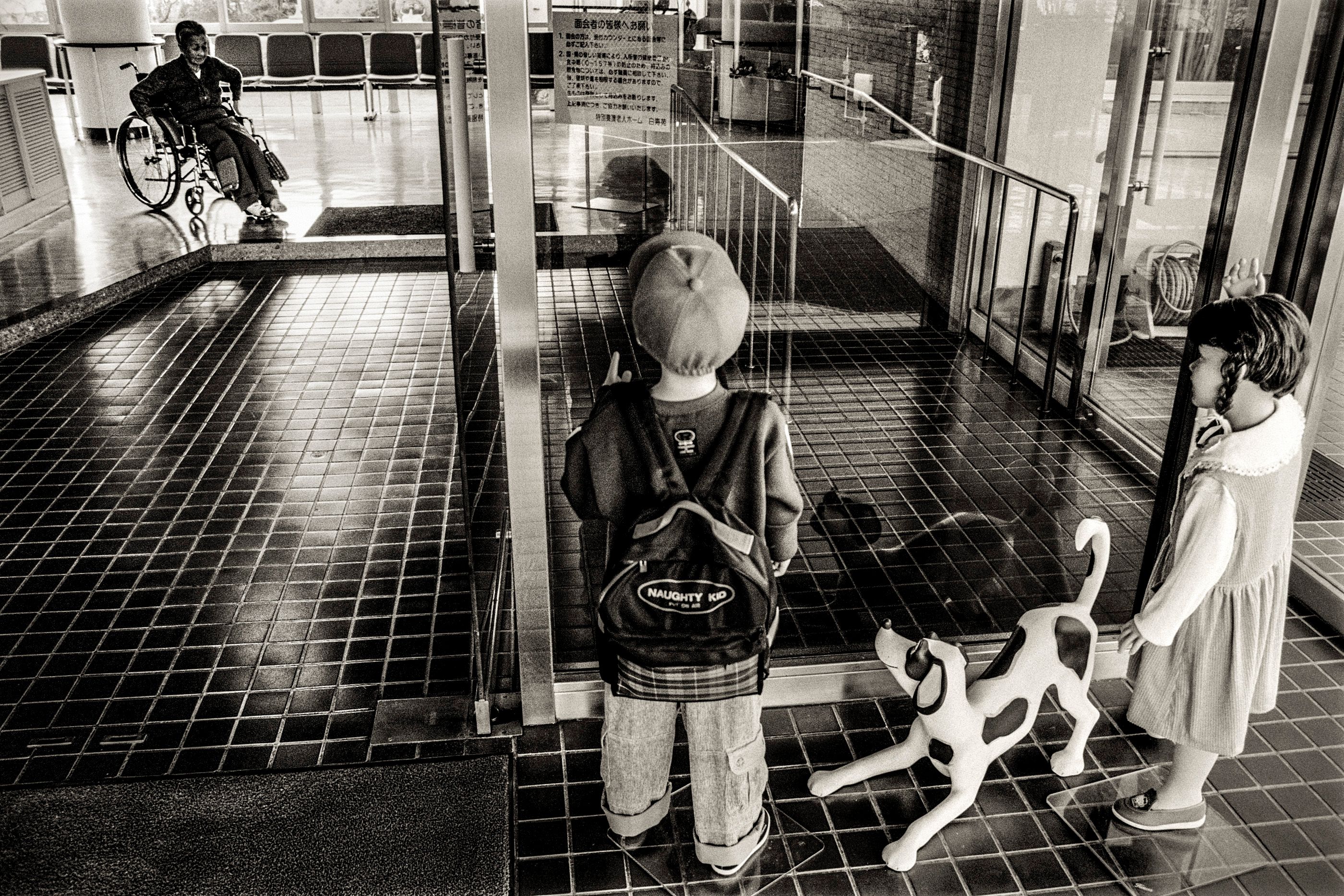

During two days in Oshima, the only children I see outdoors are a boy and a girl standing with their dog in front of the biggest of the island's eight old people's homes. Their smiling faces are upturned, their hands frozen in a perpetual wave of welcome. It takes a second glance to work out that these are not real children, but dummies. The manager of the old people's home, one of the island's biggest employers, smiles when he is asked about them. "We bought them a few years ago," he says, rather shyly, "to soften the atmosphere of the place."

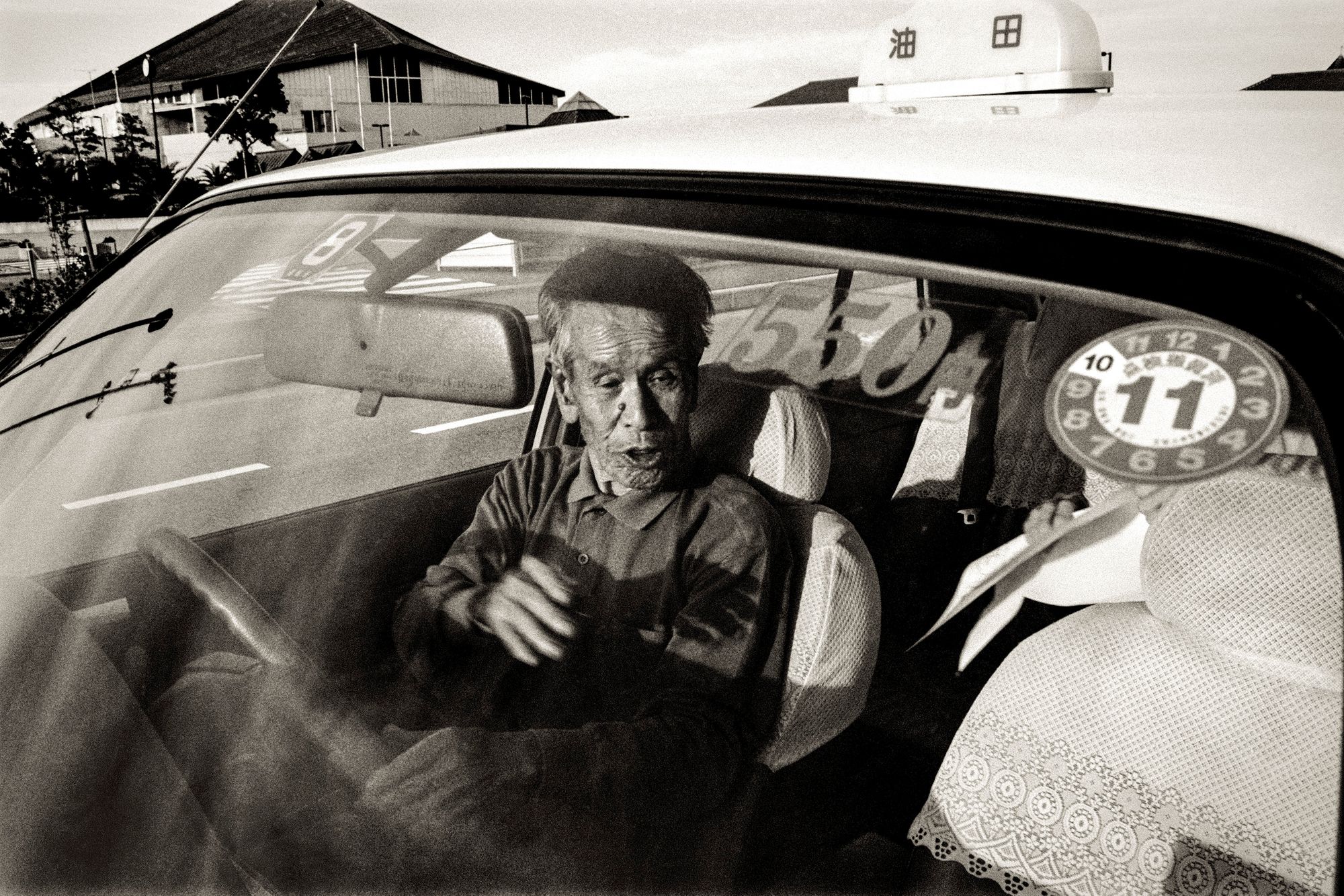

On Oshima's southern tip is Okikamuro, an island off an island off an island, with a community so old that it makes that of its larger neighbour appear youthful by comparison. Behind a small harbour is the kind of village that has almost disappeared from other parts of Japan: delicate houses of wooden boards and straw-reinforced clay, sloping gently upwards to pines and orange groves. The waters around here are rich in horse mackerel and puffer fish; in the autumn, the orchards yield armfuls of the sharp- sweet mandarin oranges called mikan. But several of the boats in the harbour, and half of the houses, are abandoned.

Tuberous wasps' nests hang from their eaves, beneath slipping tiles and exposed beams. Through the crumbling clay walls you can see tables still set with the plates and jars of their old dead inhabitants. On the wall of one is the photograph of an earnest-faced baby, who must now be in his thirties; beneath it is a calendar from 1966. "When there are two people and one dies, the house can keep going," said Toshiko Isobe, who runs the general store on the sea-front. "When there is only person, and they die, the children never want to come back and live here. The house becomes empty, and so it falls down."

Mrs Isobe's shop sells everything from biscuits to socks to toilet paper, although much of the stock looks as if it hadn't been changed, or even dusted, in years. Her husband, whose family ran this shop for longer than she can remember, died 20 years ago, and these days she is lucky to have 10 customers a day. "But this is the only store like it in this area," she says, perched on bad knees behind her till and abacus.

"Everyone says that I have to keep it up, because if I'm not here there'll be no one else. I want to keep going as long as I can still move around a bit, because it keeps me busy. If it wasn't for my pension, I couldn't make a living out of this. But with a pension it's OK."

Twenty years ago, there were 500 people living in Okikamuro; today there are 230. Logically, if the decline continues at the same rate, in another 20 years there will none at all. "It's melancholy to think of the number of people who have left the island, the faces of people who aren't here any more, because they have moved or died," says Mrs Isobe. "In 10 years perhaps there'll be no one on this street. It makes me feel sad." Mrs Isobe is 75. She runs her shop as she lives, and as almost a third of Oshima's old people live: alone.

NONE OF this has occurred suddenly, and the forces which have made Oshima what it is are at work all over the world. What makes the island so alarming is that its demography is extreme, but not freak. A lack of employment opportunities for people of working age may have accelerated the ageing process here (and contributed to a general exodus that has seen the population of, for example, Towa town, decline from 20,670 in 1945 to just under 10,000 in 1970 and a mere 5,553 today). But what has happened here will also happen, to one degree or another, throughout Japan - and in many other developed countries.

Two important things are bringing this about. Japanese people, even more than their rich contemporaries in European countries and America, are living longer and longer. The exact reasons are unclear, but a low-fat diet and improving medical care obviously have much to do with it. Life expectancy in Japan is higher than anywhere else in the world: 83.6 years for women and 77 years for men. Sixteen per cent of the population at large is over 65, and in 15 years' time this could have risen to one in four. For, as their grandparents live longer and longer, Japanese women are having fewer and fewer children.

Japan's fertility rate - the number of children which the average woman bears in a lifetime - has sunk to 1.39, and no one really seems to understand why. Limited living space, later marriage, an increase in the number of working women, low sperm counts caused by pollution and stress, or simply a loss of interest in sex among married couples - all have been suggested. Whatever the cause, Japanese are dying significantly faster than they are being born. If the downward line continues to follow the same gradient, the population will have halved by the end of the next century.

The consequences of these changes will be gradual but drastic. Culturally, Japan will abandon the emphasis on youth that currently dominates fashion and the media. Politically, it will be dominated by elderly and conservative voters. Economically, it will be stricken by a shrinking number of working tax-payers and an increase in those dependent on the medical services, welfare facilities and social security.

Demographers use a particular kind of bar-chart to illustrate the make- up of populations. The central vertical axis divides them into age-groups - from birth to age four, from five to nine, from 10 to 14 and so on. The horizontal axis expresses the numbers of people in each group, men along the left and women on the right. In a developing country, with poor standards of health care and low rates of birth control, the graph takes the form of a rough pyramid - a large number of young children diminishing with the years and reaching a narrow apex in old age. Across Japan nationally, it looks more like a spindle - a small number of younger people, with a middle-aged bulge, tailing off towards the top. But the graph for Oshima is quite different - a narrow stem of the young and middle-aged supporting a fat cluster of the elderly which contracts dramatically in the nineties and disappears in the hundreds. It looks top-heavy and unstable and slightly sinister, like a strange formation of eroded rock or a mushroom cloud.

IN SWIFT'S great novel, after his visits to the midgets of Lilliput and the giants of Brobdingnag, the hero, Lemuel Gulliver, visits a country of people who have eternal life. The immortals are called the Struldbrugs, and their great blessing turns out to be a cruel curse. Weary and exhausted and cynically embittered towards one another, they crave death, but it is always beyond their reach. This is the nightmare that Japan fears most. Among politicians and bureaucrats in Tokyo, the inexorable ageing of the population has produced an atmosphere of thinly disguised low-level panic, charged by the realisation that it is already too late to reverse these overwhelming trends.

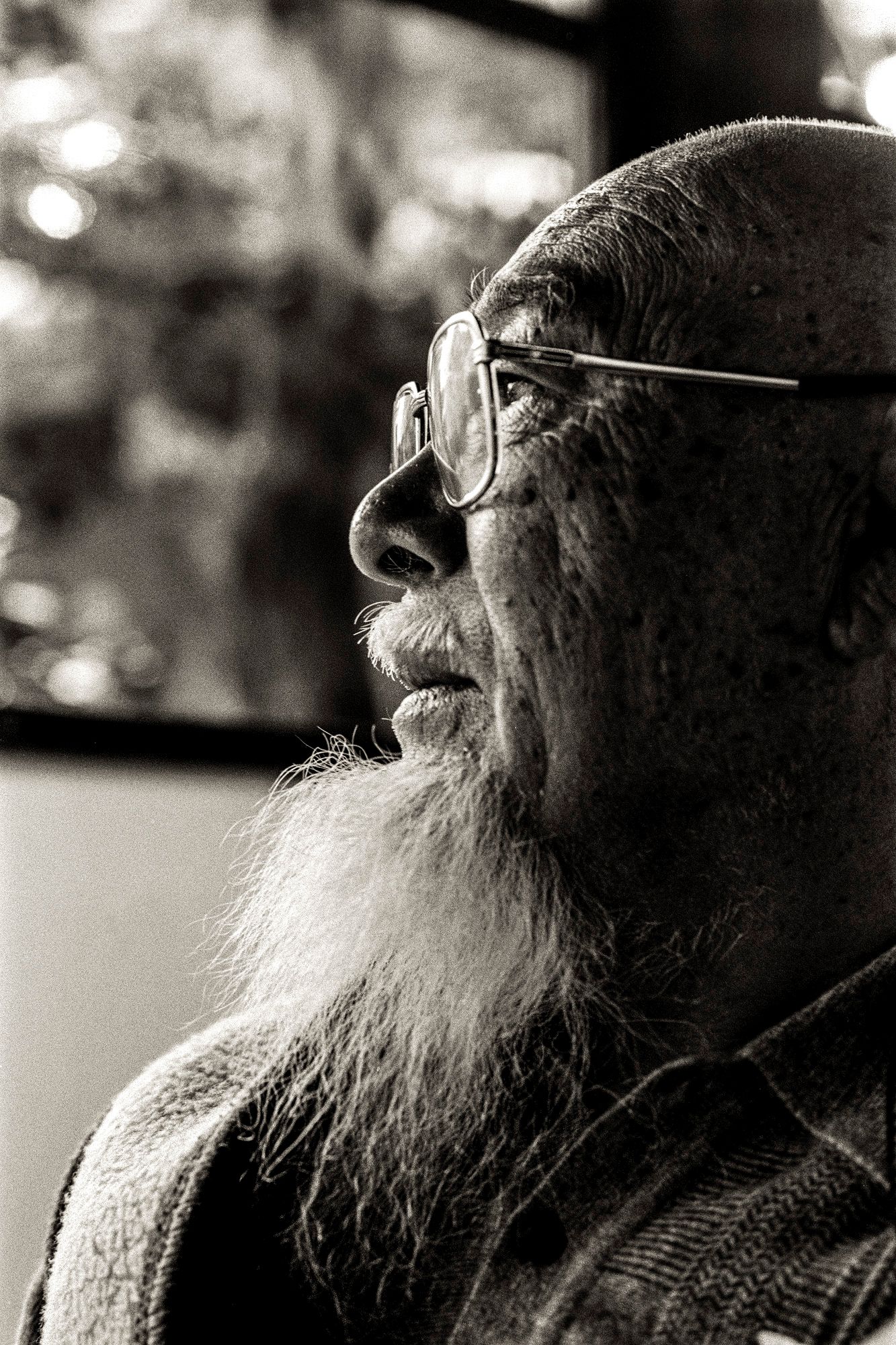

Every few months, from the big cities of Tokyo and Osaka, awful stories detail the loneliness and desperation of the urban elderly - of old people driven to suicide by poverty and isolation, and corpses which lie undiscovered for weeks. But here is the last surprise of Oshima: that, far from being lonely and embittered, its people are the most contented of Struldbrugs. Just like the young who leave, the old people who stay in Oshima have their reasons. "This isn't a place for young people," says Takeo Otani. "It's the destiny of this island. I've resigned myself to that." Mr Otani is 86, and a former head of Okikamuro's Old People's Club. His children live in Tokyo and Osaka. "When my wife died five years ago, they used to say, `Come and live with us!' But I have no friends there, apart from my children and grandchildren. My son and his wife both work, the children go to school. Life there would not be good."

Every day, Mr Otani walks up the hill to gather mikan from his trees, which he distributes among his neighbours and friends. He cooks for himself, using the recipes he acquires at a cooking class organised by the Old People's Club for recently bereaved widowers. In the afternoon he deals with Old People's Club business on his word processor. In the last hour of light, he fishes for the horse mackerel which he will eat the following day.

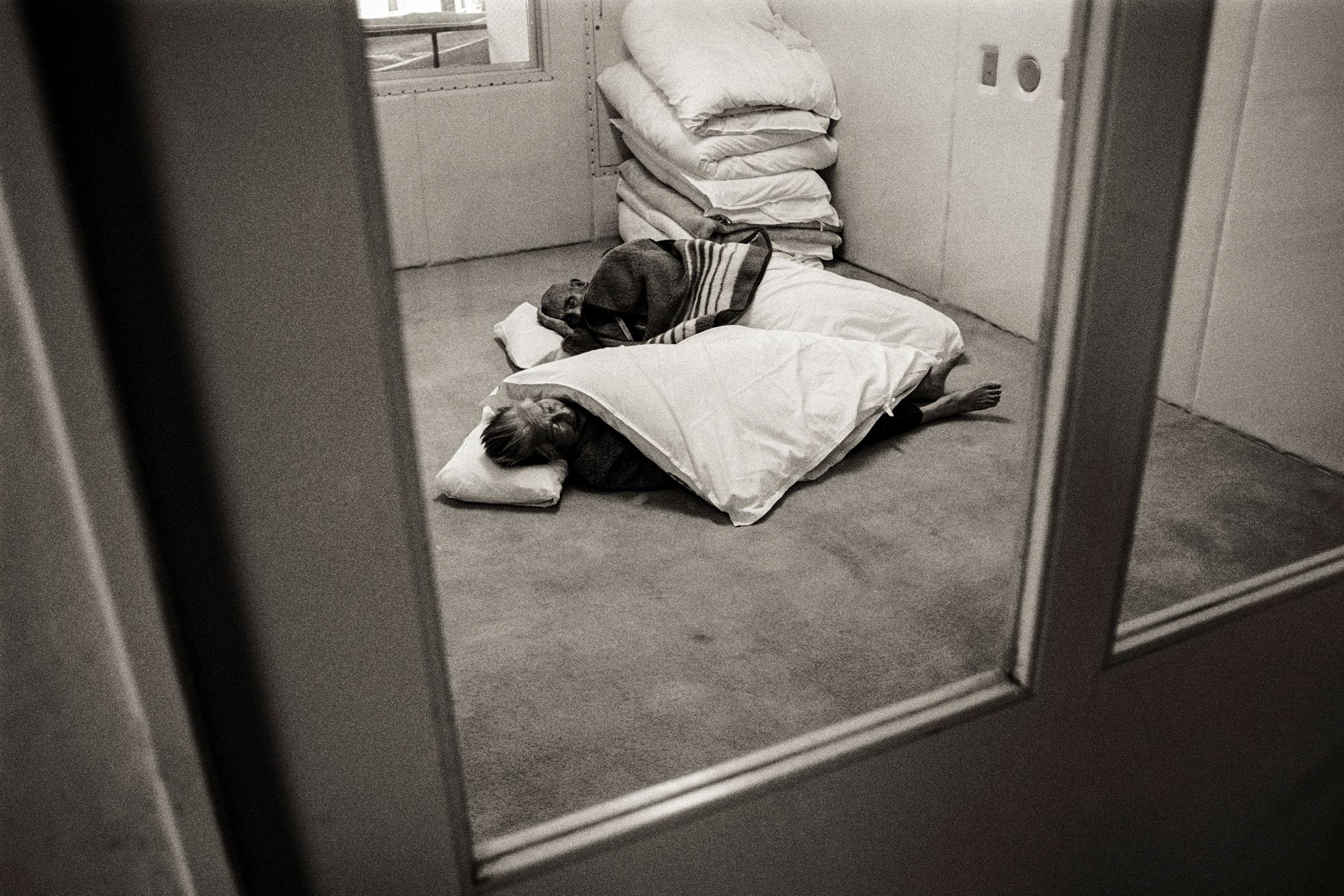

Apart from the occasional autumn typhoon, the weather on Oshima is mild. Someone stole a few coins the other week from offertory box of the Reverend Niiyama, who has a Buddhist temple on Okikamuro; but otherwise there is no crime. Almost a third of the island's old people live alone, but the lonely deaths that occur in Japan's big cities are unknown here. Instead, a pattern has emerged which is establishing itself in other parts of Japan as well: the old caring for the very old. Until the death of her 104-year- old mother three years ago, Tsurue Inokawa looked after her at home. Now she gets up at 4.30 every morning to help prepare meals-on-wheels for 100 other housebound people. She herself is 86.

There is a fashion among the elderly of Oshima for setting up "Touch- Meet Salons". Members of the Dandelion Salon enjoy dancing and karaoke; once a week, the Liveliness Salon goes swimming. The local welfare office has set up the Touch-Meet Post, which delivers letters to the elderly in person, rather than just pushing them through the letter box. If there is no sign of life after three days, action is taken. The famous Japanese propensity for group "activities" can be stifling, but in a place like Oshima it is almost certainly a life-saver. "That's the difference between here and the city," says Yoshinori Nakamoto of the Social Welfare Council. "People communicate with their neighbours, and they care about how they are. Everyone has someone as their friend, even if they are old and sick."

"What you have to realise is that an aged society is something that humans have always searched for," says Reverend Niiyama. "We have struggled for long life, and for peace that allows us to enjoy it, and for a rich country in which women can work and live lives of their own without always being burdened with children. Each element of this is something we aimed for, so now we have found it, we shouldn't be afraid of an ageing society.

"It is not a wolf which is attacking us. It is what we always wanted. By that measure, this island has the most advanced society in Japan. This is the life that all of Japan will have in the future. However we go about building the future, this is a good place to start."

Originally published in the Independent Magazine.