By the spring of 1995, I was already a year into my so-called photography "career". I had started well apparently - fresh out of a photography graduate program in 1994 in Chicago, my first assignment was a three week assignment with the legendary editor Kathy Ryan at The New York Times Magazine, hired on the basis of a project on Cambodian gangs I did in the US. By June of 1994 I had moved to Bangkok with my then girlfriend, and now my wife, Jennifer, and I had plans to base myself there and learn the ropes. Within weeks I had assignments with The New York Times in Malaysia, Thailand and Burma. Wow, this is easy!

Then the phone stopped ringing. For a year.

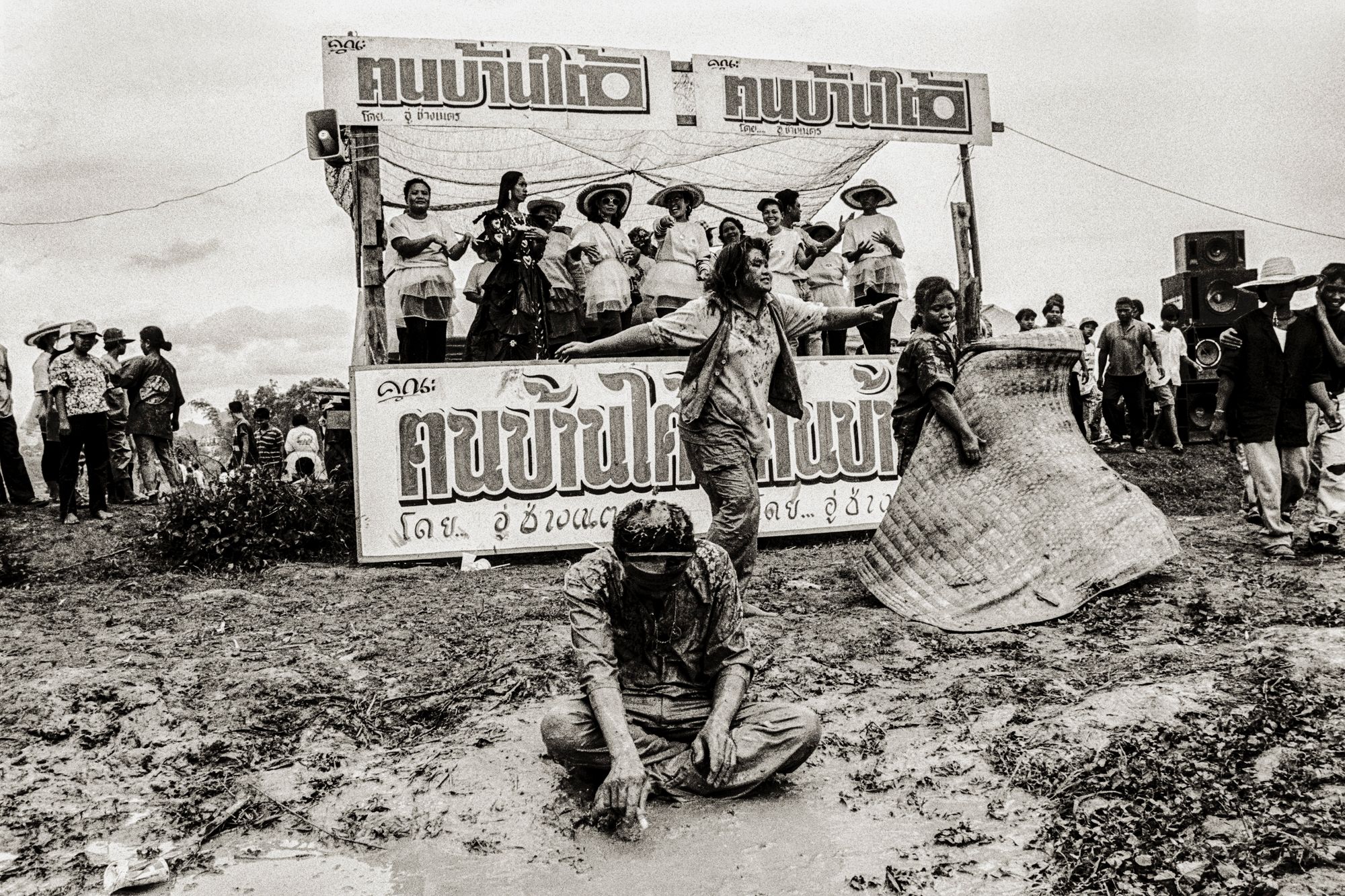

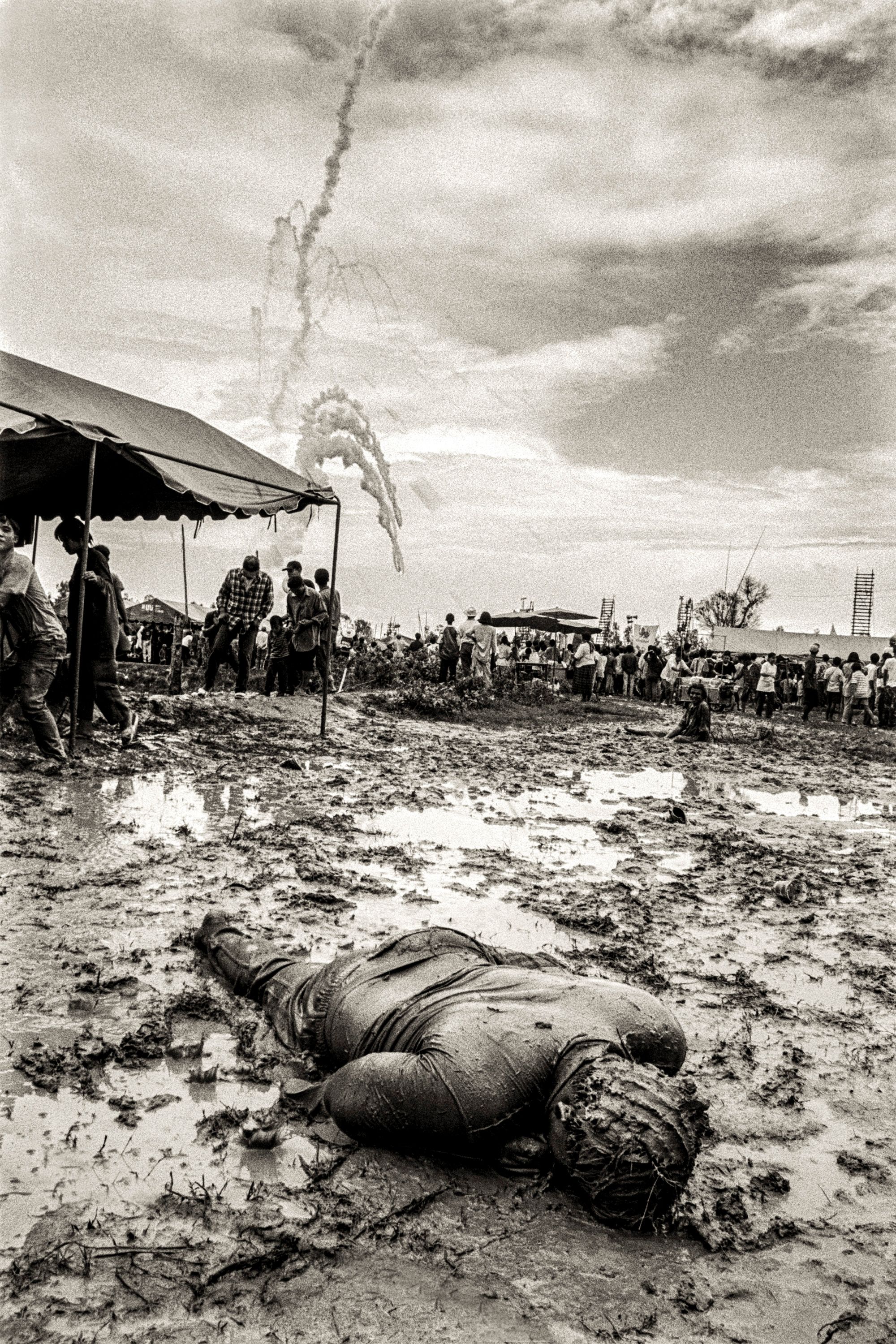

I had to sell my workhorse 80-200mm lens to pay rent. I went back to teaching English at the same school I had worked at in Bangkok in 1988 when I lived there as a student studying Thai. I did a few random assignments for the Associated Press but had no clue what they needed or how to deliver the work and was clearly not cut out for wire work. Even though our rent was only $160 a month, by May of 1995 I was close to quitting photography when a friend suggested I go to northeast Thailand, often called Isarn, and photograph the rocket festival they have there at the beginning of every rainy season. I had so little money, I had to take the cheapest, non-air conditioned bus from Bangkok, the one that stopped at every village along the entire ride, which was close to 14 hours. But the bus was filled with Isarn farmers returning home, drinking, singing and reveling the whole time. I was on the right track, and on the right bus. I was also part of the whiskey-bottle-and-fork rhythm section while my traveling companions sang and did ramwong folk dances in the aisle for most of the journey.

When I arrived in Yasothorn, the two day event was under way and I threw myself in - I had 10 rolls of Tri-X film, two cameras, two lenses (28 and 85mm) and little to lose. My Thai language skills gave me good access to rocket teams, who plied me with rice whiskey, morning, day and night. My Thai also let me skip pass organizers and police keeping tourists at a safe distance; a polite wai and a few flattering words in Thai, and I was in. When I returned to Bangkok and developed the film, and made prints, something astonishing happened. I knew I was on the right path - the work was good, but most importantly, it was the kind of work that made me want to be a photographer. Again. Later at the legendary Bangkok journalist bar The Front Page, I showed the work to my friend and fellow photographer Ben Davies who suggested I go - they were, in his opinion, some of the best images he'd seen of the festival. To this day I remember where we were sitting at the bar when he told me that.

The spark was reignited and the next 3 years in Thailand were some of the most productive years of my career, constantly working on stories, assembling edits, trying to sell them to small magazines around Asia. The assignments came back too, editors learned who I was, but I also learned how to deal with the lulls. My path as a photographer was back, simply by doing the work. What was true in 1995 is, of course, still true in 2023: Do The Work.

Images and my original text from 1995 below.